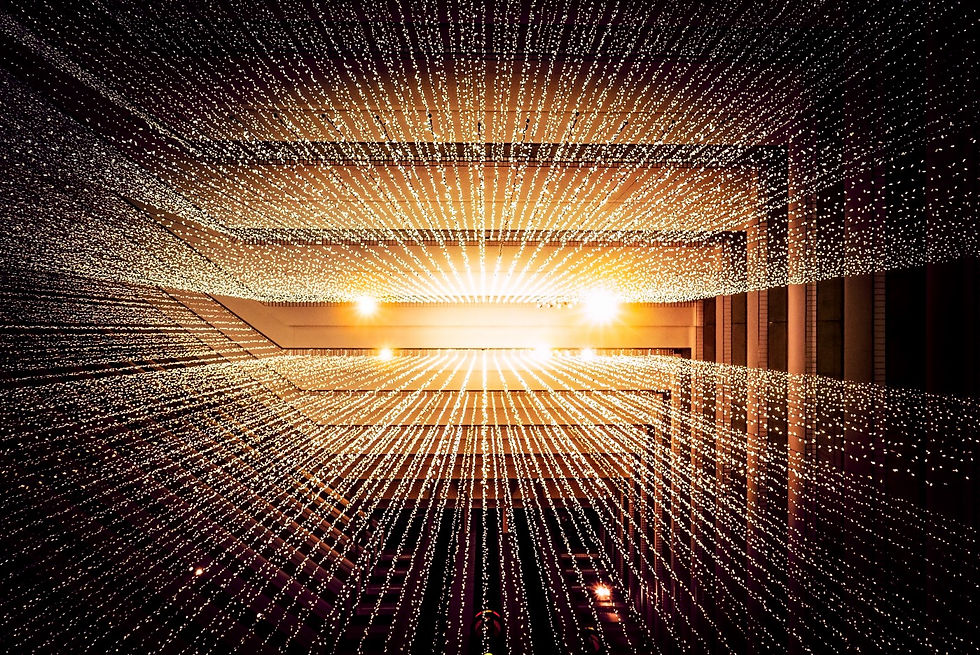

Imagine yourself confined in a container-like room. And suppose that the only way for you to look at the outside is to peek through a tiny hole. Through this small crack, you can only have a glimpse of part of the whole picture. But with a bigger window, you would be able to see the entire scene that surrounds the room and identify where you are more easily and quickly.

Better off with the bigger tool, right?

Well, this seemingly simple logic — the greater or the more, the better — apparently holds true under other completely different circumstances as well: in Big Data.

“Big Data is all about seeing and understanding the relations within and among pieces of information that, until very recently, we struggled to fully grasp.”

Don’t you think the meaning of Big Data describes the situation represented by the container room example quite well?

As we try to better understand the relationships among information, there are three major shifts of mindset happening around us, which are interlinked and often reinforce one another. Here are the three major shifts:

1. The first is being able to analyze vast amounts of data about a topic rather than being forced to go for smaller sets.

2. The second is our willingness to accept data’s messiness as we understand that exactitude is not really the aim of Big Data.

3. The third is having the desire to look for correlations instead of looking for causality.

Now, what if there was not even a small hole? Or, what if you were just unable to discover that tiny crack? This was exactly the situation for our ancestors. In the past, people did not have an adequate tool to see the world and deal with data.

Thus, very basic methods were employed to deal with this situation; for instance, counting numbers in this ancient time made use of small clay beads, which was indeed very inconvenient. This inconvenience existed in the case of larger-scale countings like census as well; these larger-scale countings, usually conducted at the state level, were costly and time-consuming. And still, it only gave out approximate information!

However, one man from Great Britain changed everything — and this great man’s name is John Graunt.

Just as you would ultimately be able to find out the room’s small crack that would allow you to see the outside world, Graunt also found out a relatively useful tool to analyze data and make predictions about bigger things. How did he do that? Well, Graunt wanted to know the population of London at the time of the plague, and this led him to devise an approach called statistics. And it turned out that statistics enabled him to “infer” the population size and also proved that extrapolating from a small sample can provide useful knowledge about the bigger general.

After this revolution, the method of random sampling began to be employed in various fields and tasks, such as when conducting censuses or political snap polls. Still, people only worked with little data because of poor tools to collect and analyze the data.

However, although sampling precision was being improved by increasing randomness, sampling was not enough to satisfy people. People didn’t like the fact that sampling doesn’t scale easily to include subcategories and doesn’t allow deeper drilling. And yup, it just seemed to be impossible — even after trying everything — to see the big, full picture of the world with the tiny, tiny hole.

But the good news is: it was not the problem of the people, it was the problem of the tool they were trying to see the world through.

Noticing this, people gradually tried to seek a tool through which they could see the big picture. They wanted to use all of the available data. One revolution in 1890 greatly contributed to this significant turn from sampling to Big Data — an American inventor Herman Hollerith came up with the idea of punch cards and tabulation machines, which marked the beginning of automated data processing.

“There still is, and always will be, a constraint on how much data we can manage, but (now) it’s far less limiting than it used to be and will become even less so as time goes on…”

After this revolution and other small and big contributions, Big Data was born, in which as much of the entire data set as possible is actively utilized. In Big Data, the more data added, the better the quality of the predictions.

"Using all the data need not be an enormous task.”

We favor Big Data to sampling due to the massive benefits Big Data brings us. Big Data is more reusable, and it allows us to analyze without blurriness, test new hypotheses at many levels of granularity, and work at an astonishing level of clarity.

You are able to see Big Data actively used in our real life. For example, a firm called Xoom which specializes in international money transfers is backed by big names in Big Data, and it succeeded in noticing a criminal group by sensing abnormalities in data trends. How cool? Analyzing all the data allowed the firm to catch a criminal group!

In addition, YouTube recommends channels and videos based on the videos each person often goes to. Youtube also informs people of what’s trending based on the number of clicks a video gets daily. McDonald’s also makes use of Big Data to collect data about in-store traffic, customer interactions, and ordering patterns. Based on these data, McDonald’s refines the menu design and training programs to attract more customers. Also, Big Data allows the company to predict the number of food lovers at a specific time of the day so that it can prepare according to the demand.

How interesting? Now, it’s the age where computers know you better than you yourself!

After reading through this journey, aren’t you prouder of the big, transparent window that reflects the world for you?

Key Takeaways:

* Big Data is understanding the relations within and among pieces of information that we struggled to fully grasp.

* The first shift of mindset is analyzing vast amounts of data.

* Random sampling doesn’t scale easily to include subcategories and doesn’t allow drilling deeper as datasets lack malleability and details.

* The more data added in big data, the better the quality of the predictions.

This article is based on the book Big Data: The Essential Guide to Work, Life, and Learning in the Age of Insight.

Such an insightful analogy! The comparison of the limited view in a container like room to the significance of Big Data in understanding relations among information is brilliant. Plumbing Services Washington